Sleeper buses and trains appear to be the right sort of environment for me to write in, it seems. Or should that be, ‘in which for me to write’? Who knows! Sorry if I am offending my literary friends with unknown grammatical offences in these blogs – ignorance of the law however is no defence against grammar nazis, of which I am one…normally! Ha!

Anyway, as I was saying, in order for me to write, an extended period of time during which we have little or no other option of entertainment or enjoyment (other than drinking, and that’s never a good idea on long distance transport (ref: delayed bus trip to La Tania circa New Year 2013/14 with a certain G MacLennan, his bottle of Jaeger, and that look in his eye!)), and a sense of perpetual motion offer the perfect conditions to recollect, remember and reflect. We’re currently trundling through Northern Thailand on our way back to Bangkok. It only seems like a month ago since we were there before. Oh, hold on…

But this blog isn’t about Bangkok, it’s about Cambodia. Crossing the border into Cambodia was an interesting affair involving much standing around, wondering if we were in the right place, and being told to wait in the corner because we refused to pay the bribe. Anyway, the Cambodian authorities now have a scan of all five of mine and Helena’s fingerprints on both hands, but we have visas and still have our 200 baht. I’ll take that as a moral victory!

We had booked a room at Downtown hostel in Siem Reap (again on the recommendation of the Lahneys, thanks guys!) and it was a great place to chill and have a party. They even had a pool – a proper pool that you could actually dive into and swim. What a luxury! With sun lounging beds strewn around it in various states of disrepair, and a slightly shabby but very functional – and well used indeed – bar built from bamboo in the corner, we seemed to have stumbled upon a little bit of travelling heaven! That’s excusing the desperate state of the single speaker sound system that they clearly abused night after night; the music gradually increasing in volume and decreasing in quality as tweeters and sub-woofers alike gave up in protest at the constant battering they were receiving.

Siem Reap is also clearly a town that is embracing the party vibe. We were a little disconcerted when we went on our first wander out into Siem Reap, and Cambodia – exciting, unusual, scary, different – to stumble upon a Hard Rock Cafe not five minutes walk from our hostel. But we were undeterred and ventured further into the town. According to the guide book, there was a ‘main street’ of sorts in Siem Reap that has so many pubs on it that the travellers and locals alike simply call it ‘Pub Street’. Now, one thing that I’m finding to be an intermittent but recurring source of frustration on this trip is the inaccuracy of various maps in the guide books. They are particularly bad at actually placing restaurants, bars and hostels in the correct places in reference to their actual physical location on the planet. They often name streets incorrectly or draw them in places where they simply don’t exist – I mean, come on, it’s not that hard is it? Surely?

So, having met a friendly girl called Gemma on the bus, we three decided to go for a meal somewhere. Pub Street seemed like a safe option for new arrivals such as ourselves, and with an extra person with us, there was suddenly a slight yet tangible pressure to find somewhere reasonable to eat. So I was espousing all the reasons why we may not find this ‘Pub Street’, ‘…because, you know, half the time you go to where it says on the map, and it’s just not there. Or it’s on the next street over, but the blob on the map is a bit ambiguous. So, you know how it is, hopefully we’ll find this place but it might not even exist at all…’ My words were trailing off into a sea of hopelessness and despair, although I needn’t have worried. As we crossed the bridge into the town centre, there it was, right before our eyes, not ‘lit up like a neon sign’ but literally – A MASSIVE NEON SIGN ACROSS THE ROAD: <<<PUB STREET!! – the series of flashing arrows pointing us down the so aptly and imaginatively nick-named street. I have never before felt so confident as to say ‘you literally can’t miss it’ when giving directions to other travellers at the hostel over the next couple of days!

The main reason for visiting Siem Reap, however, is not for Pub Street – surprising I know! It is the closest town to the vast complex of temples that are commonly referred to as Angkor Wat, although Angkor Wat itself is only one part of this ancient metropolis.

Helena and I decided to spend one day visiting the Cambodia Landmine Museum. We hired a pair of mountain bikes and headed off vaguely in the direction signalled by the guide book. The museum itself is about 25km away from Siem Reap though so it only has an arrow pointing to it off the edge of the map. On the way there, we passed an Angkor Wat ticket checking booth and spent an interesting (some might say excruciatingly frustrating) 20 minutes persuading the officials that we weren’t going to visit the temples. And yes we knew it was a long way to the museum, and yes we knew where we were going (that one was a lie), and no we didn’t have a ticket, and no we really didn’t want to see the temples, and yes we certainly could be trusted to go straight to the museum, and yes we understood that we’d be fined if we were caught inside a temple. It was quite a hot day and the negotiation had to be run by Helena as my patience waned very quickly! But eventually we were let through and carried on cycling.

Within minutes we were cycling past a ruined temple on our left and I was saying to Helena, ‘Wow, look at that!’

‘No! You mustn’t look!’ came the reply, ‘Just keep cycling!’ Moments later, there was a huge pool on out right, ‘That must be the Royal Bathing pond…’ It seems the doubts of the ticket checking staff may have been well founded..!

The Cambodia Land Mine museum is a small place that tells a very moving story – a story that should in reality never have to be told. A super condensed version is that Aki Ra, the founder of the museum, was, as a five year old child, a soldier in the Khmer Rouge who told him that his parents were dead. By the age of ten he was a child soldier, being put to work laying thousands of land mines in the jungles of Cambodia. After managing to defect and escape, he now spends his life clearing the millions of land mines that remain in the Cambodia landscape – mines that were set by himself and hundreds of others like him. The land mine museum started out at his house, where he brought back the cases of the defused mines. He also brought back children who had been maimed and orphaned by land mine explosions. Having built a new museum about 7 years ago, the museum now houses exhibits that tell Aki Ra’s story and a large school and living complex for the orphans behind it that are rightly not open to tourists. The story continues, and there are still an estimated 3,000,000 mines still live, still a potential threat to the lives of the villagers, the farmers and the children, scattered around the Cambodian landscape.

That afternoon was a pretty harrowing experience at times, but it was only the beginning in terms of what we were to see and hear about in Cambodia. To learn more and make a donation to support this worthy cause, visit http://www.cambodialandminemuseum.org

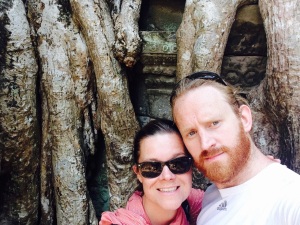

The following morning, we hired bikes again but this time our destination was the temples – and we happily bought tickets! We started at Ta Prohm, which actually turned out to be our favourite of all the temples. Huge stone faces look down from above the gates as you walk underneath, and into the temple complex. Your sense of insignificance is then only magnified by the sheer scale of the nature that has overtaken this temple – huge trees have grown up around and within the temple itself. The tops of these giants are hundreds of feet in the air but it is the roots that have created the biggest impact, working their way in between the stones of the temple structure in immeasurably small increments over the course of hundreds of years in the never ending search for water.  Roots as thick as trunks in their own right, sometimes seemingly caressing the ancient building, embracing it, preserving it, but oftentimes squeezing relentlessly and mercilessly through cracks and destroying the fabric of what once stood in supreme dominance of the environment surrounding it. It was so interesting to see not only the visual impact of the nature on the temple, not only the way that the roots and stones now seem to be inseparable, as if that is the way that they were designed, but the way that the man-made structure stood no chance over the course of time. All-powerful Mother Nature took back what is rightly hers, and didn’t worry about asking for permission! My mind wandered to the poem Ozymandias, so often on the GCSE syllabus…

Roots as thick as trunks in their own right, sometimes seemingly caressing the ancient building, embracing it, preserving it, but oftentimes squeezing relentlessly and mercilessly through cracks and destroying the fabric of what once stood in supreme dominance of the environment surrounding it. It was so interesting to see not only the visual impact of the nature on the temple, not only the way that the roots and stones now seem to be inseparable, as if that is the way that they were designed, but the way that the man-made structure stood no chance over the course of time. All-powerful Mother Nature took back what is rightly hers, and didn’t worry about asking for permission! My mind wandered to the poem Ozymandias, so often on the GCSE syllabus…

We spent the rest of the day looking around Angkor Thom, the Elephant Terrace, the Terrace of the Leper King, the Baphuon Temple, Bayon temple – with its 216 sculptured faces (I’m beginning to think this Jayavarman VII was a little bit of a narcissist) and finally Angkor Wat itself. It is undeniably and staggeringly impressive but I would agree with the guide book when it says that the sum of the parts of the rest of the complex and probably more astounding than Angkor Wat itself. My lasting impression, or thought perhaps, is that I cannot visualise this place as a living, breathing, working centre of a civilisation. It’s so cinematic in its nature, with its carved faces and vast structures (Ta Prohm was actually used as a set for Tomb Raider), that it has a sense of the unreal about it. Standing on the Terrace of the Elephants, you have to imagine the mammoth scale of ceremony that was once held in exactly that place. It literally blows your mind.

Our second stop in Cambodia was the capital, Phnom Penh. It was another overnight bus ride, and turning up at 7am, bleary eyed we stepped down from the bus to be greeted by a gaggle of taxi and tuk tuk drivers. Employing our usual tactic, we headed for the nearest coffee stand in order to avoid the melee. We got a coffee from a particularly friendly old guy at his pavement stall and, perched on tiny plastic stools, tried to figure out where we were in relation to our hostel. Realising we were hungry, we opted for breakfast instead of moving and I got up and asked the old man, ‘Err, hi, do you have a menu?’

‘No,’ he said. I was initially a little put out by his short response and was about to walk away, but he followed it up very simply with, ‘Chicken soup,’ gesturing to the stand behind him. It wasn’t a question, and moments later we were being served a piping hot bowl of chicken noodle soup, and some fresh iced jasmine tea. A beautifully simple lack of choice led to one of our favourite breakfast experiences of the trip so far! Funnily enough, we had a similar experience the following night when we went to a street barbecue stall that we’d come across. Again, no menu and the only choice – chicken or pork – was made easier as the lady had run out of chicken. Pork it is then – and it was beautiful!

However, although Phnom Penh should stand in its own right as a worthy destination, the city has a more sinister and harrowing presence on the traveller map. ‘Oh, you’re going to Phnom Penh? I guess you’re going to see S-21 and the Killing Fields then?’ Yes – sadly, that is why we’re here.

We visited both S-21 and the Killing Fields on the day we arrived. Having heard that it was ‘a tough day out’, there was – I’m a little ashamed to say – a part of us that felt it was almost better to get it over with. That’s not quite what I want to write but I can’t quite express the emotion precisely enough.

I’m not a particularly good student of history, mainly because I have a terrible memory, (well, that’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it) so I won’t start to write an essay on the historical build up to the take over of the Khmer Rouge in 1975 – you’ll be thankful to know, nor do I have a detailed understanding of the ideaology behind Pol Pot’s regime. I suppose, having visited Phnom Penh, I am only grateful that the barbaric nature of their rule only lasted just over three years. I say ‘only’ – it was far too long for hundreds of thousands of teachers, doctors, lawyers – anybody who was ‘educated’ was high risk and imprisoned or executed.

I think it is from my perspective as a teacher that S-21 is most shocking. ‘Security Prison 21’ used to be a school, and visiting it you can sense its unmistakeable architecture. It felt almost familiar to wander down the cold concrete corridors, with evenly sized rooms spaced out along the length of each; a simple layout, not dissimilar from my own school. The four buildings surround a central courtyard, a playground, but there are gravestones in it now, and a gallows that was apparently used for torture rather than execution. Quite a few of the rooms have chalk boards still screwed to the walls at the end of them, and you can imagine lessons taking place there, although as you look at it you notice metal hoops that have been cemented into the ground to which prisoners were chained in rows. The Khmer Rouge, meticulous in their work, photographed and recorded every prisoner who was detained at S-21. Now these photos line the walls, and standing display boards, in multiple rooms – like the faces of ex-students, these men, young and old alike, women and indeed children were never here to be educated. They look out at you, faces of ghosts of a past hell.

There is much to learn at and about S-21 – the exhibits are thorough and harrowing. You wonder how it all happened, how it could be allowed to happen, and you wonder if the world has learned a lesson? I suspect not. Not yet.

That afternoon, we cycled out to Choeung Ek – ‘The Killing Fields’. When the grounds and facilities of S-21 became too limited for the volume of executions that were being levied by the Khmer Rouge, the prisoners were put on the backs of trucks and taken 14km southwest to a longan orchard that had historically been a Chinese cemetery. Having been told that they were being moved to ‘alternative accommodation’, they were brought to the killing field, made to kneel on the edge of a mass grave, and bludgeoned to death. The Khmer Rouge did not wish to waste precious ammunition on executions.

Today, Choeung Ek is a remarkably peaceful place. There is an audio guide that they give you for free and the calm voice of the narrator allows you to understand the history of the place, while reflecting on your own thoughts. A side effect of the audio guide is that, since everyone is listening to it, the place is remarkably quiet. Behind a line of trees, the ground looks like a battlefield of sorts, with large crater-like holes gouged in the earth. But there was very little fight here as most of the prisoners had their hands wired together behind their backs. They know this as that is how they were found when the graves were exhumed – for you realise quickly, that that is what you are looking at – an innumerable collection of mass graves, some of which held up to 450 bodies.

The stupa that has been erected as a memorial to the atrocities that were committed at Choeung Ek is a simple, but large structure. You realise quickly that the remains of the bodies that were found have been preserved and placed in glass cases in the stupa itself. You are encouraged to go inside and look in, and remember. Remember the thousands who died there, whose skulls are lined up in row after row, on shelf above shelf, reaching high above you as you look up. Although I felt a mixed sense of fear, sadness and possibly a little bit of disgust at the graphic nature of the memorial, I came to understand that it is out of a sense of reverence and respect that the remains are displayed so openly. It is not gratuitous in the least. There is much more that could be written about these two places, but we’ll probably tell you the rest when we see you. It’s not a nice story.

Cycling back home was probably the best thing as the manic road (and we thought India was bad!) was enough to concentrate the mind. The day had indeed been a strain on the emotions but travelling is not just about having parties and lying on beaches. We feel grateful that we’ve been able to see some of these places first hand, yet still shocked at the incredibly destructive force of man. Is it power the corrupts minds? Is it money? Religion? Politics? All of these? I don’t understand how the minds of humans who co-exist with others end up with such twisted senses of morality. And yet, as I wrote earlier, the world at large has many challenges facing it… who knows what the outcome will be, and how future generations will feel when they visit the sites of our atrocities.

Cambodia – was a spiralling, wheeling, wind-milling series of twists and turns – ancient cultures morphing with the natural world, recent history playing havoc with our emotions, and amongst it all, the party hostels, no-choice menus and games of beer pong in swimming pools meant that this was a place that etched itself firmly into our memories. Next … we were off to Ho Chi Minh City to meet up with a certain Dr Tessa Oelofse. After Cambodia, we were wondering what we would find in Viet Nam…

But that’s for the next blog! We’re now on a different sleeper train to the one on which I started writing this instalment, now heading south from Bangkok to Ko Samui to meet up with Mr and Mrs Gavin Lahney. Apparently there’s a Full Moon Party soon. Shhh – nobody tell anybody that we’re in our 30’s!